I had started reading this book a few months ago as it had been in my to-do list but other things had gotten in the way. I decided to tick it off on a recent long haul flight, buying a copy from Peachpit, which by the way is my eBook source du choice as it’s one of few I’ve seen that give you the option a PDF download - up yours Adobe Digital Editions!

As its title suggests, the main message is that one’s efforts when designing a website pivot around making the experience as cognitively hurdle-free as possible.

As I had expected from its thousands of reviews, this was a great, accessible, and entertaining read on web usability.

This post lists the main takeaways I got from the book. By no means a summary of the book but a set of points memorable in my case based on my experiences designing and developing web applications.

General comments

The book is written in a no fuss, relaxed way and in this spirit I found it nice that it kicked off with a no fuss definition of usability. He states that usability (in any context) means that:

A person of average (or even below average) ability and experience can figure out how to use the thing to accomplish something without it being more trouble than it's worth.

This resonated with me as my experience to date has been mostly designing and developing very domain-specific web applications and I’ve often wondered about how “usable” they are given the user base almost invariably already has some domain knowledge before they use the app. A few tests observing domain-inexperienced users play with it suggest they are OK, but I know they could be better. I assume that’s always the case.

The majority of the examples Krug presents relate to web sites and after the first few chapters I found myself wondering how well his points translate to web applications. After a few chapters I could concluded that most of what he says does apply to web applications if one thinks of them as a collection of related websites. That helped me think about it, but I recognise it isn’t a perfect mental framework.

Takeaways

Don’t make people think

The most obvious takeaway but a good one to repeat in one’s head constantly I think. I find this is easiest to forget when writing text like instructions in dialogs or confirmation pages. I think it’s harder to overlook when designing components or the flow a page as that usually involves self-checking during iterations of the component as it is designed.

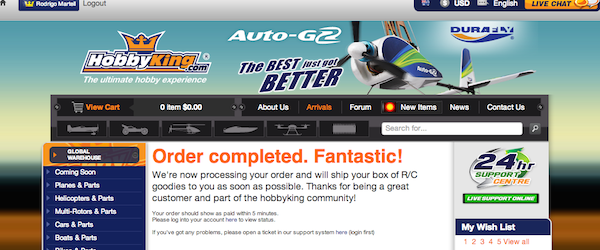

For example, you’ll likely expend a fair amount of cognitive effort in designing a fancy multi-stage form and be a bit too tired at the end of the process when you tidy up the confirmation text at the end of the form. A good example of this I found was Hobby King’s purchase confirmation page.

It may be hard to see in the screenshot but the tiny font at the bottom contains a two links : one to login to view the order and one to their support ticket system. Wait, what? You’ve logged me out after checking out? Why did you do that? In any event, that conflicts with the state suggested by the upper left of the page. Apart from being a bit wordy and using awful colors and font sizes (personal opinion there), the page gets me every time, wondering if my order actually went through given it seemingly thinks I’m logged out after the checkout process. I find I always double check my account to make sure the order has gone through.

There is no “average” web user

Based on his experience watching people use the Web Krug makes the observation that:

ALL WEB USERS ARE UNIQUE.

AND ALL WEB USE IS BASICALLY IDIOSYNCRATIC.

At first glance I disagreed with this as the trend-finder in me felt the had to be at least some things average web users do predictably, like expect website logos on the top left of a site to be clickable, or look for navigation on the top or sides of the page. Krug’s point however, was more aimed at finer points of web design where assumptions on how “most users” use the web creep into design despite the real possibility of those assumptions being off for the particular site being designed. The solution is, of course, user testing to provide some quantiative evidence for or against these assumptions.

I recall one instance where a web application I was developing on required files to be uploaded. I decided we’d use jQuery fileUpload to provide this functionality as a drag and drop kind of action where a file would get dropped into the page and it would be uploaded to the server for processing. I discovered, however that when it was implemented the page where the uploads were meant to happen didn’t have any visual cues to tell users where to drop the file.

Based on his instinct and way of using the application the developer had felt it was obvious that you would drag the file and drop it anywhere on the page to trigger the upload. I thought it wasn’t obvious enough and we left it as it was while silently disagreeing. Neither of us had solid evidence for our positions on the issue until weeks later when I watched users interacting with the application (admittedly live already!) having real trouble figuring out where to just drag and drop files to. This was a problem particularly for older users.

I quickly added a bit of code that day to make it obvious there was a designated area and both young and older users were able to get it, hopefully making them think less. It could very well be that another set of users in a different domain would have just gotten the drag and drop anywhere on the page, but it took an admittedly bum-backwards simple user test to figure out what was best for our set of users in our domain.

Most people muddle through life your site

It’s funny, I’d not given much thought to how often I muddle through things until I started thinking of how I use web sites. My initial approach is to jump in and try a site out without giving much thought to understanding too much about what’s going on or how it works. According to Krug, this is a common approach and something to keep in mind when designing web sites. I related to this a few important points:

-

Seach-centric vs clicking users. Visitors to sites tend to explore by predominantly searching or predominantly clicking through menus/links until they find what they’re after. Having said that, you can get anything in between, so a design that caters for both ends of the spectrum can help.

-

Lots of clicks are OK as long as they are meaningful. I had always shied away from burying things behind more than a few clicks. I’ve found this to be a constraint I invariably break. According to Krug, the number of clicks isn’t so much an issue so long as each click takes one closer to your objective.

-

First impressions count. A lot. A bad first impression (e.g. not being able to find navigation elements or a malfunctioning button) can hang around like a bad smell even if the remainder of the site or session works well.

The above I think may contradict the previous section on there not being an average web user. However, I choose to see them as rules of thumb that are validated or rejected after a bit of user testing.

Do usability tests, often

This is perhaps my greatest retrospective fault when developing web applications. I’ve mostly been in the position of developing applications I would use and as such do a lot of self-testing. It doesn’t, however, replace testing with other users, which I’ve done but not as often as I could have. Krug emphasises that usability testing can be done pretty well at any stage of the development process and it can be done cheaply and relatively quickly. The general process involves in essence sitting next to someone in front of your application and asking them to complete a few tasks while your record the session (notes or actual screencast).

I’ve now heard of multiple success stories of this simple approach and am determined to do it more often.

Accessibility

In all honesty, I hadn’t given accessibility much thought until reading the later part of Krug’s book. I’d been insulated from this as I’ve to date known the audience of my web applications would not have accessibility issues. As a matter of habit though, it is an arrogant approach especially when you don’t know anything about who is on the other side of the screen. I would understand this being shelved if it was time-consuming but it seems the majority of the time it’s just a matter of forming good habits like never leaving blank alt attributes in img tags. I must make this a habit for me.