Late last year I bought a cheap 3-channel foam remote control (RC) plane (including remote) on a daily deal site. I’ve always loved planes and had been attracted to RC flying since I was a kid but thought it was too expensive a hobby to take on seriously. For $30 delivered this was a great plane but after flying it into a tree on the third flight I was left wanting more.

I decided to begin looking more seriously at RC planes and was surprised at how cheap they were. I found myself, however, confronted with a crap ton (technical term) of terminology and basic concepts I didn’t understand. My knowledge of electronics was (and still is to a great extent) dismal. I was fortunate enough to meet a very knowledgeable and generous RC pilot, Robin Schmitt, while walking my dog at the park one day. He has been instrumental in sharing his knowledge, setting me on the right track to learn more after every flight. He’s also great company when flying on weekends. Thanks Robin!

This post is aimed at someone who might be looking to get started with RC planes with close to zero knowledge of electronics. I will include as many links and resources I found useful as I can. It is in essence a semi-structured dump of knowledge I would’ve liked to have at hand when I was starting out.

How RC planes work

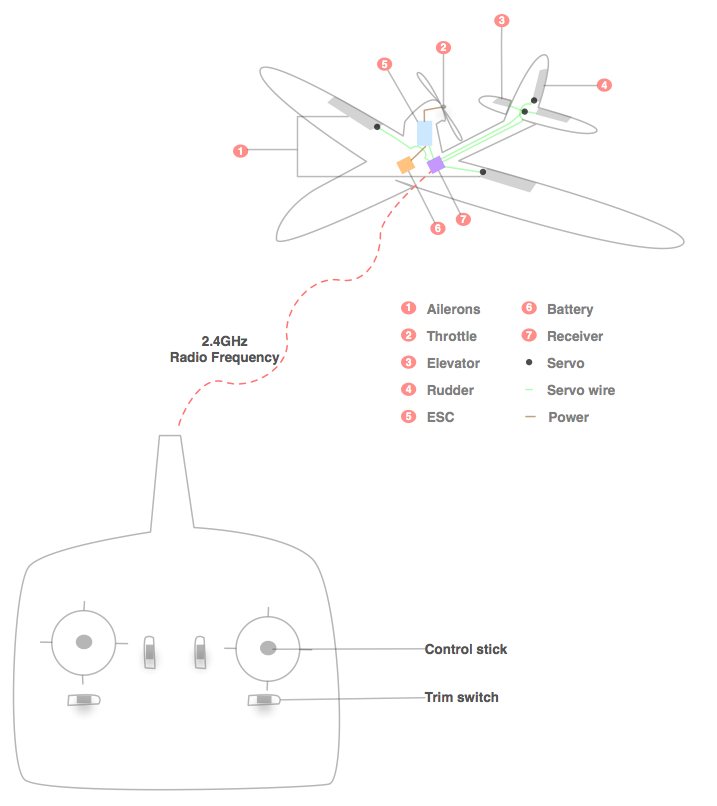

This may seem obvious, but I think it’s worth a little diagram to get a basic visual on the moving parts. You can refer to this diagram as you read the rest of this post.

An RC remote is most commonly referred to as a Transmitter or TX for short. It converts your controls’ movements (e.g. up, down, left, right) into radio waves that get picked up by your plane’s Receiver or RX for short, which relays the signal to the appropriate component to move. The component that receives the “move” (my terminology) signal can be anything, but in the most basic of planes they are either a servo or an Electronic Speed Controller or ESC for short.

A servo is a small (like 1cm tall and 1cm wide) plastic box with a motor and gears inside it that move a little plastic arm at the top, typically just left, right and back to a center position. This plastic arm is connected to a control surface (e.g. elevator) via some metal rods. The end result of all this is that when the RX relays a signal to the servo, the servo moves the arm, which in turn moves the rod, which in turn moves the control surface and the plane reacts.

An ESC does exactly what the name suggests: control the speed of your motor given the signal sent to it by the TX via the RX. It is your throttle, essentially.

I’ll use this basic description of how RC planes work in the remainder of the post, expanding on what I think is important information for beginners like me.

The Transmitter (TX) and receiver (RX)

Transmitters can transmit to the RX over a range of frequencies, but RC models typically use the 2.4GHz frequency. This means that your TX (after binding with your RX) will be sending instructions over a 2.4GHz frequency and both the TX and RX must be “yelling” and “listening” respectively over the same frequency. This frequency apparently gives about 1.5Km line of sight (LOS) control range, but you should keep your plane far, far closer than that when you’re starting so you should never need anywhere near that range.

You may notice that many brands of TXs out on the market run on the 2.4GHz frequency, as do RXs. How do these not interfere with each other? Well one must first select an RX that “speaks” one’s TX’s brand’s language (the way radio waves are interpreted by the RX), plus one must “bind” an RX to a TX in order to use them together. Binding essentially pairs up your TX to your RX, creating a private (you hope) tunnel of communication between the two.

There are a lot of transmitters with all manner of bells and whistles, which can make selecting one a daunting process. To make it easier just remember that all you need your TX for when starting out is to control four things (assuming you use the rudder): throttle, elevator, ailerons (1 channel does both), and rudder. You’ll notice a remote states a number of “channels” it can transmit on. This means the number of things on the plane it can control. As stated, you’ll want/need at least four to begin with. Later on you might find use for more channels (e.g. landing gear, bomb drops, etc), so if you get a TX with more than four channels it’s no big deal, you just won’t use past four initially.

If your plane doesn’t already come with a TX I would suggest a cheap TX+RX combo from HobbyKing.com like this one as it takes the guess work out of finding compatible RXs with TXs since some brands are compatible with others but not all.

There is one more thing you must carefully think about when choosing your first TX: its “mode”. A TX has two sticks, which can both move up/down and left/right (that gives the magic four channels from earlier, 2 sticks x 2 directions/stick = 4 channels). Here is an illustration of the different configurations (modes) TXs come in. The right choice comes down to personal preference. I chose Mode 2 because my first plane came with a Mode 2 remote and so it stuck. I like that when I hand launch (rarely successfully!) with Mode 2 I can control the throttle with my left hand as a throw the plane with my right. Mode 1 pilots I see do this the opposite way (throw with the left hand) and control the throttle with their mouth or chin. I find this awkward, but it comes down to personal preference. Bear in mind, however, that it’ll likely be a bit of an ask to retrain your brain to use the other Mode down the track. Not impossible, but cognitively taxing.

Power

Getting a handle on batteries for the plane was the most difficult thing for me when I started out. My utter ignorance of electrical concepts made me paranoid I’d either kill myself or cause my plane to go up in a ball of fire because I didn’t know what I was doing. The latter would have been almost worth the risk as it would have look awesome!

Batteries for the TX you first get are likely just your household AAs so no confusion there. Your plane, however, will likely have some range of battery sizes and types it can take that one should adhere to.

Electric RC planes these days most commonly use Lithium-Polymer ( LiPo ) batteries. You’ll see them everywhere on sites in all sizes. They are referred to as a “pack” since they are in essence a pack of cells (sacks with LiPo “juice” inside them) connected to each other in series via some internal wiring. Each cell has a nominal voltage level of 3.7V, but when you charge them up they’ll go towards the 4V level per cell. A pack has a capacity (measured in milli Amp hours, mAh) which means a level of current (measured in Amperes or Amps or simply A) that can be drawn from it before it is emptied. These few bits of information let you decipher the posted information for most of the batteries you see out there and help you select the right one for your plane. When you’re starting, your plane might already come with a battery, but if it doesn’t, the manual should tell you what the specs of the kind of battery it can take.

An example of a battery I own is the ZIPPY Compact 850mAh 3S 25C Lipo Pack. In plain English, this means it is a LiPo (battery) pack with 3 cells connected to each other in series (the 3S part of the title) with a capacity of 850mAh (or 0.85 Amps). Because it has 3 cells and each has a nominal voltage of 3.7V, the total Voltage of this pack would be 3 cells x 3.7V/cell = 11.1V out of the proverbial box. If it were a 2S pack, the total voltage would be 2 cells x 3.7V/cell = 7.4V. Your motor via the ESC will have a certain amount of draw it will impose on your battery to get the plane up and banging around, so it pays to have a higher capacity battery. The problem is, the higher the capacity the bigger the packs get, thus weighing down your plane. So, it’s a balancing act.

There is one figure I left out in the previous example: charge/discharge rate. The mysetrious 25C part of the battery example simply means that the pack can be safely discharged at a current level up to 25 times its stated capacity (0.85 Amps). To convert from mAh to A simply multiply by 1000. So, in the example above the maximum safe continuous draw that can be applied to the pack is 25 x (1000 x 850mAh) = 25 x 0.85A = 21.25A or 20A to be safe. Your ESC likely says it can draw up to something like 15A and can handle up to 3S packs and so this battery would be OK for it.

A now trivial thing confused me with batteries once I bought them and that’s how/where to connect them to the plane. I figured out that the battery connects to the ESC, which in turn connects to the RX, giving the rest of the RX power to move all the other controls.

Battery packs typically have two sets of wires coming out of them: a power set and a balance set (more on the latter later). The power set can come with different kinds of connectors. The most popular are JST, XT60 and Deans. These all do the same thing in terms of allowing electricity to flow from battery to ESC, they just look different and clearly don’t connect to other ilk. It is possible that your ESC may not have the same connector type as your battery. This stung me when I got on of my planes as its ESC had an XT60 connector but my battery had a JST connector. If this is the case you’ll obviously need an adapter of some sort, which you can either make (I didn’t have the tools to do so) or just head to eBay or HobbyKing.com and pick up a simple and cheap one there. I went the eBay option.

I mentioned the balance plug in the battery but didn’t explain what it does. The balance plug (a white, square plastic plug) enables a balancing-capable LiPo battery charger to monitor the voltage on each cell as it charges the battery to make sure it is putting even voltage across all cells. Charging a LiPo without balancing could apparently lead to some nasty surprises like a bit of fire here and there from pumping too much voltage into one cell or when discharging below a “safe” level (3V/cell seems to be the standard “do not go below” level and 4.2V/cell the “do not go above” level). Check out this and this video to get an idea of the kind of fire ball they can (un)pleasantly surprise you with.

So using the balance plug while charging is all well and good, but during flight then does the balance plug just sit there with nothing plugged into it? Yes, but it doesn’t have to. I would strongly suggest you spend $2 and get a low voltage beeper, which when connected to the balance plug during flight monitors the voltage level on each cell of the pack and beeps really, really loudly when any one of your cells drops below 3.3V. If the battery has been balanced during charging and the ESC draws power evenly (not sure this part is correct, but I’m going with it) then the beeping should be close to indicating that all cells are at a low voltage. When you hear the beep you know it’s time to line up for a landing or crash depending on your skill level and your luck. In the absence of a beeper one would have to do some arithmetic/guessing to keep an eye on the flight time and come down when you “think” you’d be low on voltage. That takes away from the fun a bit I think.

There are a few things to look out for after using your batteries. The first is that after your flight you must remember to disconnect the battery from the ESC and unplug any beepers or anything else that was plugged into the balance port. I once forgot to disconnect the beeper and came home two days later to hear it going off in the study at an almost inaudible level. It had been drawing a tiny amount of power from the battery and had drained the battery to about 3V per cell. Dumb and dangerous - see fire references above. I learnt my lesson.

The second is that you should store LiPos at 3.7V per cell if you’re not going to use them for a while (say a week or more). This apparently helps look after their longevity but is also a safety precaution. I typically charge my LiPos on a Friday night before heading out on Saturday morning for a flight. Any unused LiPos get put on the charger in discharge mode on Saturday night to bring them down to 3.7V per cell and any used ones get charged up to 3.7V per cell. I initially bought what I thought was a nifty charger but realised while using it that it didn’t have a discharge mode, which sucked. I later bought a new one that had a storage function meaning it drains or charges a battery up/down to 3.7V per cell. Easy. For peace of mind (and wife), I bought a few LiPo-safe fire proof bags to store and charge my batteries just in case I leave the house having stuffed one up and our house (which we don’t own) and beloved dog (whom we’re fixated with) don’t go on a slow roast until we get back from work.

The plane

Obviously, you’ll need an RC plane. If you go to sites like HobbyKing.com you’ll notice all kinds of abbreviations for plane types and materials.

The “in” material to go for is Expanded PolyOlefin (EPO) foam when you’re starting out. It’s cheap, durable and tends to snap back to its original shape when dealt a blow. If it breaks, a little bit of hot glue gets you back in the air in no time. There are heaps of other materials out there like balsa wood and carbon fiber, but foam is your friend when learning and perhaps for ever! I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve smashed my plane and it has either survived or has been brought back to almost new with a bit of hot glue.

Planes come in different states of “readiness” to fly out of the box. You will see Ready To Fly (RTF) models, which mean you just pull the plane out of the box and get flying. It will likely have a remote that’s already bound to the receiver on the plane. Just connect the battery and fly! Almost Ready To Fly (ARF) planes usually have the structure of the plane mostly put together but need you to put things in it like servos, an ESC, etc. Plug And Fly (PNF) models come with all servos and bits installed but require you to BYO receiver and remote. There are other kinds of X And Fly states that I can’t remember, but when starting out you’ll want to go for the RTFs or PNFs to keep it simple.

The kind of plane to select when starting I would suggest to be something large (but not too large) that is reported to glide well. The reason for the largeness is that you’ll have a nice naturally stable flight. The reason for staying away from too large a plane is that in my experience the crashes seem to be more disastrous with larger planes. My first plane was an FMS 1280 (i.e. 1280mm wing span). I crashed it about 5 times before its first successful flight and every crash hurt, a lot. Also, hand-launching too big a plane can be an unnerving experience.

I would recommend getting a plane with a propeller at the back, a so-called pusher prop because it pushes your plane through the air rather than pull it as it would if the propeller was at the front. The reason for this is simple: you’ll likely snap the prop on a landing or two.

A final thing to decide on is gear. I was in two minds about getting a plane with or without landing gear. My view is that if you have a flat-ish surface to take off and land from gear can help with take-off at least. I hand-launch my planes as they don’t have gear and it’s an awkward experience. I often ask my friend Robin to launch it for me as I’ve stuffed it up too many times. I can’t help but think taking off with gear would feel more controlled and natural rather than the quick chuck and nervous grabbing of the remote to get the plane climbing level. Having said that, I’ve never used a plane with gear and if you don’t have a flat surface to take off from gear I think it would end in tears very quickly. Landing is another story, it’ll likely be challenging either way, gear or no gear.

Wait! Don’t buy a plane just yet.

So after all this talk about planes and how simple it is you’d be tempted to go out and get a plane and give it a shot. That’s exactly what I did and it ended in absolute tears as I was completely inexperienced with the controls.

After witnessing the disaster of my first flight my friend Robin suggested I get a basic remote to use with a simulator to get used to the controls. Your brain is likely not trained to handle a plane the way a remote demands, especially when a plane is flying towards you rather than away from you as the ailerons and rudder are reversed. On a simulator you can crash as much as you like until you get good enough to give it a shot in real life. I bought a Spektrum DX5e 2.4GHz 5-channel TX and a copy of the Phoenix R/C simulator. I bought it as a package from a hobby shop here in Melbourne but later realised you can buy the package or the TX and simulator separately online for a fraction of the price. I got ripped off.

The simulator is made by Horizon Hobby (I think) and it comes pre-loaded with the models they make. It includes electric as well as turbine jets and helicopters. The physical components of the package are simply a TX, a cable that plugs into the back of it (a headphone lead head) with the other end plugging into your computer’s USB port, and an install DVD.

All my computers are Macs and although they claim Phoenix sim runs on Macs it’s a half-truth. To run on a Mac you have to install a Windows virtual machine (VM) first, install Windows, and then install the simulator on the VM. A bit of a pain. I would have preferred a native OS X application. I installed Parallels Desktop on my MacMini, created a VM and installed Windows 7 on it then shoved the Phoenix simulator into it to get going. There was a particularly tricky step in getting the VM to recognise the TX plugged into the USB port I remember. My friend Deo figured it out but I forget what it was. I remember it being somewhere in the VM’s settings, something like checking “peripheral pass-through” or some option sounding like that. If you get stuck on that step I’m happy to help you if you get in touch with a few screenshots to jolt my memory.

Once you fly and crash a few hundred times in the simulator you’ll be ready to put an order for a plane and crash in real life! The main difference between the simulator and real life is nerves. That’s how good the simulator is. Seriously.

Shopping list

If you’ve made it this far down the post it’s likely you’re genuinely interested in getting started and will take my advice on training with the simulator first, right? I would have liked to have a little shopping list handed to me to get started so here is one to consider. It is by no means the recommendation of an expert or the best way to go, just my recommendation based on my limited experience and with some biases based on what I’ve tried. Obviously it’s your choice on where and what to get so I’ll keep it generic.

- 1 x Plane. I’m in love with the Freewing Spirit Mini Sport Glider (featured at the top of the post halfway through a repairs session). It is stable, glides for ages, has a low stall speed, and the folding prop, although not a pusher as I suggested earlier, helps when landing as I don’t use power when touching down. It is re-configurable to a pusher prop if you like, but you have to get a separate motor for that. It’s also cheap (AUD 70 or so). It’s a PNF so you’ll need to BYO TX and RX.

- 1 x TX. I have the Spektrum DX5e 2.4GHz 5-channel as it came as a package with the Phoenix simulator. It’s a great remote to start with I think. At the great recommendation of my friend Robin I’ve upgraded to a FrSky Taranis TX, but you’ll likely not want to sink the $200-odd into a radio first up. Have a look on eBay or similar for second hand Spektrum radios and simulators, maybe even as a package. There are bound to be heaps.

- 1 x RX. If you buy an RTF you’ll probably not need an RX. However, you’ll need one if you get a PNF like the Spirit. Make sure the RX you get is compatible with your TX’s brand. Since I have the DX5e TX, I got the OrangeRx R620 6Ch 2.4Ghz Receiver as it’s compatible with it(I looked it up beforehand).

- 1 x RX satellite receiver. This was another gem of advice from my friend Robin. A satellite receiver simply plugs into the side of your RX and has another tiny RX on the other end of a long cable. This enables you to place a sort of backup RX in case the main RX temporarily stops receiving. It is well worth the few dollars of investment. I got the OrangeRx R100 Spektrum JR DSM2 Compatible Satellite Receiver as I knew it would work with my RX.

- 3+ x Batteries. This will depend on the specifications of the plane you get. For the Spirit I initially got a few ZIPPY Compact 850mAh 3S 25C Lipo Packs which work very well although it takes a fair bit of wiggling around in the battery compartment to make all the bits fit ending with a very tight fit. I later got a few Turnigy nano tech 950mah 3S 25-50C Lipo Packs and they work even better as they are not as fat as the Zippy 850mAh packs. You’ll want at least 3 packs to get a decent flight out on the field as each will keep you up for around 10 minutes depending on how hard you smash the throttle.

- 2 x connectors. Make sure you have connectors to connect your battery to your plane’s ESC. For example, the Spirit’s ESC has an XT60 connector but all the batteries I bought have JST connectors. I had to get an XT60 to JST connector to fly. Hobby King didn’t tell me about this in the product description. Annoying. I say get 2 or more just to have some spares.

- 1 x Lipo pack Voltage checker. This simply lets you check a pack’s total voltage as well as the voltage on each cell. I got a few of these. They are handy if you ever mix up charged and discharged batteries, you simply plug the checker into the battery’s balance lead and it will beep and display the voltages.

- 2 x Low Voltage LiPo Pack Beeper. These are cheap so you might as well get a few. Here is an example. You can get these anywhere. This particular one will monitor 2-6 cell LiPos.

- 1 x LiPo Charger. I have two and my favourite is the Imax B6 because of its ability to discharge LiPos down to a safe voltage level for storage. Whatever charger you go for make sure it capable of balance-charging LiPos. Also make sure your charger has a connector for your battery’s connector. Usually they’ll come with a few. The Imax B6 for example, comes with a JST lead which means I can easily charge my 950mAh 3S batteries as they have JST connectors.

- 2 x Fireproof bags. I have two LiPo-safe fire proof bags. I use one to keep my LiPos stored for long periods of time and another I use to take charged ones to the field. This simply prevents me from mixing them up. I also use one, obviously, while chargin my LiPos.

- 1 x Hot glue gun + glue sticks. You can get these at heaps of places. Hobby King sell them if you want to go there. You’ll need it to do some repairs after you crash (you WILL crash).

Last bits of advice

Before you get up in the air, here is a quick checklist to go through every time:

-

Center of gravity (CG/CoG). Your plane will likely tell you how far from the wings’ leading edge is its center of gravity. If you rest the plane on your fingers by its center of gravity and it is well balanced it should settle leveled - not tip forward or back. If it’s not, you need to re-arrange things inside, maybe move the battery a bit, until you get it to level when balanced on your fingers. A well balanced plane will be easy to fly and launch. One that is not will crash very quickly! Check the CoG before every flight! I haven’t in the past. Dumb.

-

Check your controls. Make sure that all your controls move the right control surfaces (ailerons, rudder, elevator, etc.) in the right direction. There’s nothing worse than hand launching and pulling back on the stick to climb, for example, and realising the controls are reversed! This has happened to me a few times and I’ve learnt my lesson now. Don’t let it happen to you. Your TX will likely have little switches to let you reverse your controls.

-

Get some height!. As soon as you launch get some height. Don’t turn or get fancy until you have enough height to recover from sloppy turns or loops. It’s surprising how quickly things can turn to custard at what you think is a high altitude. A mid to high altitude forgives sloppy flights, low altitude does not.

-

Trim your plane. Not all planes are perfect and sometimes you’ll notice that when you release your controls and all control surfaces are meant to go back to their central position some may be off a bit. I notice on the Spirit the ailerons are slightly off to the left naturally (after a few crashes). This would make the plane have a tendency to bank to the right. On your TX, you’ll notice a few switches on the X and Y axis next to each stick. These are the trim switches. They simply let you make tiny adjustments to the central position of the sticks to account for these little “off” adjustments. I add a bit of trim on the Spirit until I see the ailerons perfectly aligned with the rest of the wing when the controls are released. When I launch the thing flights straight as an arrow.

-

Launch and land into the wind. It’s far easier to control a plane flying into the wind than with it. Make sure you get a handle on where the wind is blowing and throw into it. When landing, land against it with minimal throttle and definitely no throttle when about to touch down. Try to see if you can “flare” it - slow down and essentially stall just before you git the ground.

-

Hand launch at a slight upward angle. I hate hand launching. The few successful times I’ve done it I’ve done it by not throwing too hard, applying enough throttle so it feels like it wants to pull from my hand and throw it as if I wanted to pass it to someone. I’ve had some spectacular crashes by throwing too hard or at a downward angle. It’s best if you get someone to launch for you.

-

Keep the plane in front of you at all times. It’s surprisingly disconcerting when the plane flies overhead. Your brain, or at least mine, can’t rewire itself quickly enough and you’ll likely end up wiggling your controls every which way, losing altitude in the process and crashing!

-

Put your name and number on the plane. Another simple nugget of wisdom from my friend Robin. If you put your plane up a tree and can’t get to it you’ll be grateful if it comes down days later with the wind and someone finds it and they can call you to return it. The tree part has happened to be before but not the call. I did a SAR mission the day later and found it on the ground thankfully.

-

Disconnect battery post-flight. Don’t leave the ESC connected to the battery after a flight and be sure to disconnect the beeper from the balance lead too. I’ve wrecked a few batteries by forgetting to do this.

-

Watch out for messed up depth perception! When flying your plane around it’s hard to gauge from the ground how far away you are from obstacles like trees, especially when all you have behind the plane is white or cloudy skies. I put my Spirit straight into a tree about 4 storeys high last weekend because of this issue. I thought I was miles away from the tree but I obviously wasn’t. Hilarious! To be safe, fly above any obstacles no matter how far you think you may be from them!

That’s it! I hope you have a great time getting into RC flying. It’s an incredibly rewarding hobby. I’ve learned so much and have a blast smashing and flying my planes. I’d love to hear your stories and experiences if you get into it too! You can get in touch through the comments or email me.

I’m getting into First Person View (FPV) flying now, which requires a bit more investment. I’ll be sure to post up my experiences.

Finally, here a few links I’ve learned a stack from by watching or reading regularly:

- RCModelReviews.com. I don’t know the guy’s name, but his site and YouTube channel are fantastic. He explains things in a very accessible manner and is brimming with electronics knowledge. He’s also a Kiwi, which I instantly like.

- RCGroups.com. There are a few other forums like this one but this one seems pretty active. It looks horrible, like it was teleported from the 1990s, but it’s full of helpful and knowledgeable people. No question is too stupid or basic and no problem impossible.

- Raul Hsiao’s RC Flipboard. It has some interesting articles here and there even if I don’t fully understand their contents.